by Beth Levine | Oct 2, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, procrastination, public speaking

Last week, I lost my voice. Literally, I couldn’t talk. Laryngitis.

Naturally, I joked about it: The ironies of a communication coach not being able to speak – what good am I in this condition? What a pleasure and relief for my family – finally, a break and some much-wished-for silence! My own vocal chords were on strike – was it something I said?

I also wondered. When will it come back – a day, a week, longer? Who am I without my voice? Am I relegated to communicating digitally only? What did people with laryngitis do before texting and emailing?

I will admit, sudden onset of laryngitis prompted some panic and an existential crisis: Whoa, where did this come from, what did I do to bring this on? What would I do if I had to deliver a speech or presentation in this condition? Cancel, reschedule, or create a killer PowerPoint or video? How could I turn this seemingly negative event into a positive? (Maybe blog about it?) My livelihood depends on my voice, what would I do if this persisted?

Turns out, I was still me; I had the same thoughts, ideas, and feelings. I just couldn’t share them – vocally, that is. It also turns out, the people around me were at a little bit of a loss without the all-too-familiar sound that drove through my larynx – my news, my bad jokes, my unsolicited opinions and everything else I rattle off in the course of a day. It was quite interesting to observe how people reacted to my inability to speak, including the pharmacist who, perhaps in an attempt to empathetically mirror my limitations, gradually dropped his own voice to a raspy whisper to answer my barely audible questions.

The experience made me think about voice and the fact that it’s not my voice that I lost, it was only my ability to talk. I couldn’t talk. But I had a voice and could give voice without being able to make much sound. I could communicate. So as with any other change that occurs in life – for the better or the worse – I decided that, if this stayed with me, I would adapt. I would still communicate and spread my ideas (like the gospel of #audience-centricity!) through writing. Maybe I would work on another book and share my thoughts that way instead of through speaking engagements? Maybe I would become a speechwriter, creating the actual words for speakers instead of coaching them to formulate and deliver their own? Either way, not being able to talk was not going to be the end of me.

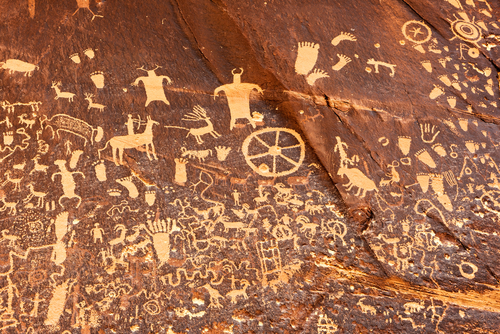

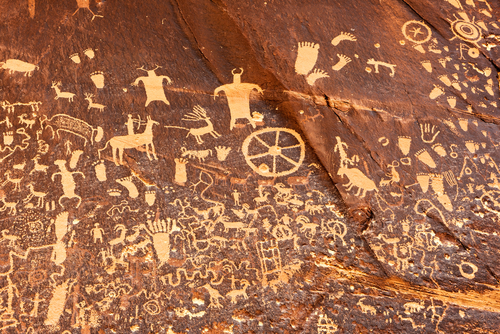

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of #brevity!). Communication is the constant, it has evolved in infinite ways over the years, and adaptation is a constant too. Think about how we have communicated news for example. News was once shared via petroglyphs etched into rock and then eventually via newsprint on paper and currently via electronic transmission on a screen. And there are other examples as well, most notably the arts – visual arts, music, dance – all of which give voice and communicate but not necessarily through talking. Voice, which can and should be carefully cultivated and deployed, is something we all have no matter what. The various methods of communication at our disposal is how we share our precious voices.

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of #brevity!). Communication is the constant, it has evolved in infinite ways over the years, and adaptation is a constant too. Think about how we have communicated news for example. News was once shared via petroglyphs etched into rock and then eventually via newsprint on paper and currently via electronic transmission on a screen. And there are other examples as well, most notably the arts – visual arts, music, dance – all of which give voice and communicate but not necessarily through talking. Voice, which can and should be carefully cultivated and deployed, is something we all have no matter what. The various methods of communication at our disposal is how we share our precious voices.

P.S. About two days later, my voice returned – albeit not in fighting condition and still on the mend. Nevertheless, existential crisis averted and lesson learned: I never lost my voice and I never will.

by Beth Levine | Sep 20, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, public speaking

What does it take to go from being a pretty darn good speaker – well organized, prepared, on point – to being a great speaker? To being someone who is compelling, thought-provoking, thoroughly engaging, and memorable?

What does it take to go from being a pretty darn good speaker – well organized, prepared, on point – to being a great speaker? To being someone who is compelling, thought-provoking, thoroughly engaging, and memorable?

It takes getting naked. Yep, baring it all. Opening up. Sharing. Being vulnerable. Being real.

Audiences crave earthy, gritty, revealing, personal. They want to be drawn in, they want to see and know. Let’s face it, it’s what we’ve become accustomed to in our digitally oriented lives [think: social media]. All that openness and sharing – even the cringy oversharing – has created an expectation and an appetite for not just the what, where and how, but also for the how does it feel.

It’s perfectly acceptable and more than adequate to speak and be organized, prepared and totally on point. In fact, it’s way more than adequate (since too few speakers are!). It makes you good, really really good.

But to be great? That requires you to open up. Connect with your audiences, let them see and know you. Share your failures as well as your successes, share your fears as well as your hopes, share your vulnerabilities as well as your strengths and passions.

Share what makes you doubt yourself and what makes you tick, what scares you and what excites you. Share what you regret as well as what you are proud of. Share what gets you motivated in the morning as well as what you dread. Be relatable.

There’s a lot to be gained – and nothing to be lost – by connecting with your audiences on a deeper level. Make a note of the reactions and comments you get from people after you bare it all. I’m willing to bet it will result in more robust feedback and far greater buy-in and engagement. And that’s the difference between good and great speaking.

by Beth Levine | Sep 6, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, procrastination, public speaking

Last week, I was delivering a workshop on Executive Presence and Communication to a group of high-potential executive women at a large financial services firm. As always, I encouraged the group to share relevant stories and anecdotes at any time during our half-day together.

Last week, I was delivering a workshop on Executive Presence and Communication to a group of high-potential executive women at a large financial services firm. As always, I encouraged the group to share relevant stories and anecdotes at any time during our half-day together.

During the segment in which we addressed the special challenges of being commanding and confident on conference calls and in videoconferences, one of the women spoke up to ask a question:

She started by sharing a story from the day before about a presentation she had made that became an extremely frustrating and disappointing experience. Her presentation was a demo; half of the audience was in the room and half on the phone, with everyone looking at the same screen. She had prepared for a week. As she described it, she began the presentation and, not a few minutes into it, a male colleague who was on the phone jumped in and took over most of the rest of the talking.

Her question for me and the group was, “what should I or could I have done to stop him?” She noted that he had a company-wide reputation for talking over others and out of turn and she characterized it as a bad case of mansplaining.

Was this a case of mansplaining? Maybe, but it’s hard to say since both genders are guilty of this sort of thing. But for sure it was a case of what I call hijacking. So let’s talk about a few ways to stop hijackers in meetings and presentations:

-

Set agreements and be clear about roles and responsibilities in the meeting or presentation with colleagues in advance. If it needs to be a co-presenting situation, then be specific about that in the meeting invite so everyone knows, and also be deliberate in how the preparation work is divided (i.e. make sure everyone who is presenting carries a proportionate load of the prep work). If the presentation is solely yours, make that known too by letting attendees know there will only be one speaker, how long you plan to speak for, how long Q&A will be, and that there will be others on the team present to help fill in during Q&A.

-

Use a Focal Point that helps establish what’s going to happen during the meeting and what the desired outcome is. For example, in a presentation like the one above, in which there’s a demo to introduce new software, and other team members are in on the call, the Opening/Focal Point might sound something like this: “I will be walking you through the demo, which should take about 15 minutes. After that, we will have another 15 minutes to answer your questions and fortunately several team members [names] are also here and can help answer your questions. By the end, I am hoping you’ll feel like you have a solid introduction to the new software, which should make it considerably easier for you once we go live.”

The Focal Point sets clear expectations and gives you a “home base” to return to in the event of a hijacking. In other words, you can always break in on your hijacking colleague’s stolen air time and say, “Rob, I know you’re as eager as I am to make sure everyone appreciates all the advantages of this new software but let me get through these initial screens so that everyone gets the same solid introduction and then you can add to what I’ve gone over once we break for Q&A.”

-

If you’ve done the best you can do by employing the above suggestions and you still get hijacked, then I would revert to directness wrapped in good manners, which is a nice way of saying, go ahead and interrupt the hijacker! Wait for the person to pause or take a breath and then interrupt directly and politely. For example, “Rob, thanks for sharing your input, you’ve been a great contributor to the team that’s put this together. Now, if we look at the screen where I left off, you’ll notice the navigation … “

At the end of the day, hijackers are usually known quantities in an organization and when they do it repeatedly and predictably, it’s a poor reflection on them, not you. Nonetheless, especially if you’re anticipating the possibility of being hijacked, then you would be wise to plan ahead with the suggestions I shared above. Good luck out there!

by Beth Levine | Aug 16, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, public speaking, smartmouth talks!

Stories – or anecdotes, examples, case studies – are the absolute best way to illustrate a point, even in a business presentation.

Stories – or anecdotes, examples, case studies – are the absolute best way to illustrate a point, even in a business presentation.

When crafted well, they illustrate and support your messages better than anything else. Stories make an emotional connection to your audience that sticks with them long after you finish talking.

Here are 3 rules of thumb that apply to using stories in your communications:

1. STORIES NEED TO DIRECTLY SUPPORT A POINT. In other words, you may have a favorite story that you love to tell, and that’s great, but it must be constructed in a such a way that it works its way to a “punch line” that reinforces the message point you are trying to support. You can’t assume the audience will make that connection on their own, you have to spell it out and tie it together for them.

2. PREPARATION IS ABSOLUTELY NECESSARY. Rather than simply reminding yourself to tell a certain story during your presentation, you need to map out the story to avoid getting lost in the details while telling it (every story has more details than you have time to share!). I have watched too many speakers derail a perfectly good 15-minute presentation by telling a story that went on and on until – before they knew it – an additional 10 minutes of air time had been consumed.

3. SIMPLE IS MORE EFFECTIVE THAN COMPLICATED. This is true of most communications but certainly true of stories – despite the temptation to “spin a yarn” for your audience. Unless you’re a comedian or a professional storyteller, you’ll want to keep your stories simple.

Keeping them simple means paring down and prioritizing the detail. Think about composing your stories in this 3-3-3 format:

-

3 sentences describing the situation;

-

3 sentences revealing the dramatic tension (e.g. something unexpected, complications, competing factors); and

-

3 sentences outlining the resolution, which should help you tie back – in that punch line kind of a way – to the point you were illustrating.

And finally, be sure to cue your audience when you’re beginning and ending a story. For those in the audience who might not be paying close attention, you have the opportunity to reignite interest with your own appropriate versions of “Once upon a time” and “The end” – those timeless story cues that signal the open and close of something special.

by Beth Levine | Aug 1, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, public speaking

Managing Q&A effectively requires you to have a good offensive game strategy. What this means is being mentally ready with an approach for how you want to field and answer questions no matter what you get asked.

Managing Q&A effectively requires you to have a good offensive game strategy. What this means is being mentally ready with an approach for how you want to field and answer questions no matter what you get asked.

Three things are important to keep in mind before we get into Q&A game strategy:

- Q&A is quite possibly your only guaranteed opportunity to know you are answering your audience’s WIIFM (what’s-in-it-for-me) needs, so embrace it!

- You want to field as many questions as you can, from as many audience members as you can, so keep your answers concise.

- It is TOTALLY OKAY not to know an answer, just say so and then offer to find the answer and get back to the person asking.

Your 5-point offensive game strategy:

1. Pause for one or two seconds after the question is asked to collect your thoughts so you can execute on points 2-5 below.

2. Ask yourself, was that a question or a speech? Speeches may not require more than an acknowledgment. If it’s a combination of a speech followed by a question, your best tack is to just answer the question.

3. Don’t focus on the words used in the question, instead search for the theme of the question. In other words, don’t be baited by and then respond to negative language. Listen for the bigger picture theme of the question, it’s a much better springboard to an answer.

4. Find one of your message points that aligns with the theme and begin your answer with a message point. Message points are great springboards, they set context so you can provide meaningful information in your responses.

5. Bridge or redirect, if necessary, back to one of your message points or to your topic. Bridging isn’t evading, it’s getting back on topic.

Q&A can be tricky and it’s always an unknown, but look at it as a triple-bonus – it’s when you get to connect most directly with your audience, it’s when you get to weave in material you might have mistakenly omitted during your presentation, and it’s when you get to reinforce your key points.

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of #brevity!). Communication is the constant, it has evolved in infinite ways over the years, and adaptation is a constant too. Think about how we have communicated news for example. News was once shared via petroglyphs etched into rock and then eventually via newsprint on paper and currently via electronic transmission on a screen. And there are other examples as well, most notably the arts – visual arts, music, dance – all of which give voice and communicate but not necessarily through talking. Voice, which can and should be carefully cultivated and deployed, is something we all have no matter what. The various methods of communication at our disposal is how we share our precious voices.

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of #brevity!). Communication is the constant, it has evolved in infinite ways over the years, and adaptation is a constant too. Think about how we have communicated news for example. News was once shared via petroglyphs etched into rock and then eventually via newsprint on paper and currently via electronic transmission on a screen. And there are other examples as well, most notably the arts – visual arts, music, dance – all of which give voice and communicate but not necessarily through talking. Voice, which can and should be carefully cultivated and deployed, is something we all have no matter what. The various methods of communication at our disposal is how we share our precious voices.

What does it take to go from being a pretty darn good speaker – well organized, prepared, on point – to being a great speaker? To being someone who is compelling, thought-provoking, thoroughly engaging, and memorable?

What does it take to go from being a pretty darn good speaker – well organized, prepared, on point – to being a great speaker? To being someone who is compelling, thought-provoking, thoroughly engaging, and memorable?

Last week, I was delivering a workshop on Executive Presence and Communication to a group of high-potential executive women at a large financial services firm. As always, I encouraged the group to share relevant stories and anecdotes at any time during our half-day together.

Last week, I was delivering a workshop on Executive Presence and Communication to a group of high-potential executive women at a large financial services firm. As always, I encouraged the group to share relevant stories and anecdotes at any time during our half-day together.

Stories – or anecdotes, examples, case studies – are the absolute best way to illustrate a point, even in a business presentation.

Stories – or anecdotes, examples, case studies – are the absolute best way to illustrate a point, even in a business presentation.

Managing Q&A effectively requires you to have a good offensive game strategy. What this means is being mentally ready with an approach for how you want to field and answer questions no matter what you get asked.

Managing Q&A effectively requires you to have a good offensive game strategy. What this means is being mentally ready with an approach for how you want to field and answer questions no matter what you get asked.