by Beth Levine | Sep 18, 2021 | preparing for a presentation, procrastination, public speaking

Three Tips to Overcome Public Speaking Nerves

Do you get nervous about speaking in public? Sometimes? Always? Let’s see what we’re even talking about here.

Do you get nervous about speaking in public? Sometimes? Always? Let’s see what we’re even talking about here.

One way Webster’s Dictionary describes nerves is “marked by strength of thought, feeling, or style: spirited.” That doesn’t sound like such a bad thing, does it? I think it sounds kind of promising. And that’s exactly the point.

Nervous energy is not negative energy. It’s positive. It’s your body’s adrenaline getting you ready to do a killer job. You just have to embrace it and understand it is a natural part of the experience.

The good news about the adrenaline rush you feel at the beginning of your talk

– even if it’s making you short on breath or sick to your stomach – is that it’s going to level off. There is research as well as anecdotal evidence that nervousness fades in the first two minutes.

So, here are 3 tips for you for those first 120 seconds:

1. Accept, rather than resist, that your nerves will come with you to the front of the room – kind of like a constant companion. And know that they’ll begin to dissolve in a matter of seconds.

2. Choreograph your opening in a way that allows you to share the floor with your audience and gives you a chance to inhale and exhale – and maybe even relax a wee bit. One example of this is opening with a question for the audience and soliciting some input from them. Engaging the audience takes pressure off you and gives you a feeling of control that helps your nerves dissipate more quickly.

3. Even if you don’t have a lot of time for rehearsing, set aside a little time to practice your opening. If you are familiar and comfortable with your opening, and you practice delivering it in a deliberately slow manner, you just might be able to compensate for the adrenaline that makes you flustered and that makes you speed talk.

Nerves happen. They’re natural. They’re energy. And they’re temporary.

by Beth Levine | Oct 2, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, procrastination, public speaking

Last week, I lost my voice. Literally, I couldn’t talk. Laryngitis.

Naturally, I joked about it: The ironies of a communication coach not being able to speak – what good am I in this condition? What a pleasure and relief for my family – finally, a break and some much-wished-for silence! My own vocal chords were on strike – was it something I said?

I also wondered. When will it come back – a day, a week, longer? Who am I without my voice? Am I relegated to communicating digitally only? What did people with laryngitis do before texting and emailing?

I will admit, sudden onset of laryngitis prompted some panic and an existential crisis: Whoa, where did this come from, what did I do to bring this on? What would I do if I had to deliver a speech or presentation in this condition? Cancel, reschedule, or create a killer PowerPoint or video? How could I turn this seemingly negative event into a positive? (Maybe blog about it?) My livelihood depends on my voice, what would I do if this persisted?

Turns out, I was still me; I had the same thoughts, ideas, and feelings. I just couldn’t share them – vocally, that is. It also turns out, the people around me were at a little bit of a loss without the all-too-familiar sound that drove through my larynx – my news, my bad jokes, my unsolicited opinions and everything else I rattle off in the course of a day. It was quite interesting to observe how people reacted to my inability to speak, including the pharmacist who, perhaps in an attempt to empathetically mirror my limitations, gradually dropped his own voice to a raspy whisper to answer my barely audible questions.

The experience made me think about voice and the fact that it’s not my voice that I lost, it was only my ability to talk. I couldn’t talk. But I had a voice and could give voice without being able to make much sound. I could communicate. So as with any other change that occurs in life – for the better or the worse – I decided that, if this stayed with me, I would adapt. I would still communicate and spread my ideas (like the gospel of #audience-centricity!) through writing. Maybe I would work on another book and share my thoughts that way instead of through speaking engagements? Maybe I would become a speechwriter, creating the actual words for speakers instead of coaching them to formulate and deliver their own? Either way, not being able to talk was not going to be the end of me.

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of #brevity!). Communication is the constant, it has evolved in infinite ways over the years, and adaptation is a constant too. Think about how we have communicated news for example. News was once shared via petroglyphs etched into rock and then eventually via newsprint on paper and currently via electronic transmission on a screen. And there are other examples as well, most notably the arts – visual arts, music, dance – all of which give voice and communicate but not necessarily through talking. Voice, which can and should be carefully cultivated and deployed, is something we all have no matter what. The various methods of communication at our disposal is how we share our precious voices.

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of #brevity!). Communication is the constant, it has evolved in infinite ways over the years, and adaptation is a constant too. Think about how we have communicated news for example. News was once shared via petroglyphs etched into rock and then eventually via newsprint on paper and currently via electronic transmission on a screen. And there are other examples as well, most notably the arts – visual arts, music, dance – all of which give voice and communicate but not necessarily through talking. Voice, which can and should be carefully cultivated and deployed, is something we all have no matter what. The various methods of communication at our disposal is how we share our precious voices.

P.S. About two days later, my voice returned – albeit not in fighting condition and still on the mend. Nevertheless, existential crisis averted and lesson learned: I never lost my voice and I never will.

by Beth Levine | Sep 6, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, procrastination, public speaking

Last week, I was delivering a workshop on Executive Presence and Communication to a group of high-potential executive women at a large financial services firm. As always, I encouraged the group to share relevant stories and anecdotes at any time during our half-day together.

Last week, I was delivering a workshop on Executive Presence and Communication to a group of high-potential executive women at a large financial services firm. As always, I encouraged the group to share relevant stories and anecdotes at any time during our half-day together.

During the segment in which we addressed the special challenges of being commanding and confident on conference calls and in videoconferences, one of the women spoke up to ask a question:

She started by sharing a story from the day before about a presentation she had made that became an extremely frustrating and disappointing experience. Her presentation was a demo; half of the audience was in the room and half on the phone, with everyone looking at the same screen. She had prepared for a week. As she described it, she began the presentation and, not a few minutes into it, a male colleague who was on the phone jumped in and took over most of the rest of the talking.

Her question for me and the group was, “what should I or could I have done to stop him?” She noted that he had a company-wide reputation for talking over others and out of turn and she characterized it as a bad case of mansplaining.

Was this a case of mansplaining? Maybe, but it’s hard to say since both genders are guilty of this sort of thing. But for sure it was a case of what I call hijacking. So let’s talk about a few ways to stop hijackers in meetings and presentations:

-

Set agreements and be clear about roles and responsibilities in the meeting or presentation with colleagues in advance. If it needs to be a co-presenting situation, then be specific about that in the meeting invite so everyone knows, and also be deliberate in how the preparation work is divided (i.e. make sure everyone who is presenting carries a proportionate load of the prep work). If the presentation is solely yours, make that known too by letting attendees know there will only be one speaker, how long you plan to speak for, how long Q&A will be, and that there will be others on the team present to help fill in during Q&A.

-

Use a Focal Point that helps establish what’s going to happen during the meeting and what the desired outcome is. For example, in a presentation like the one above, in which there’s a demo to introduce new software, and other team members are in on the call, the Opening/Focal Point might sound something like this: “I will be walking you through the demo, which should take about 15 minutes. After that, we will have another 15 minutes to answer your questions and fortunately several team members [names] are also here and can help answer your questions. By the end, I am hoping you’ll feel like you have a solid introduction to the new software, which should make it considerably easier for you once we go live.”

The Focal Point sets clear expectations and gives you a “home base” to return to in the event of a hijacking. In other words, you can always break in on your hijacking colleague’s stolen air time and say, “Rob, I know you’re as eager as I am to make sure everyone appreciates all the advantages of this new software but let me get through these initial screens so that everyone gets the same solid introduction and then you can add to what I’ve gone over once we break for Q&A.”

-

If you’ve done the best you can do by employing the above suggestions and you still get hijacked, then I would revert to directness wrapped in good manners, which is a nice way of saying, go ahead and interrupt the hijacker! Wait for the person to pause or take a breath and then interrupt directly and politely. For example, “Rob, thanks for sharing your input, you’ve been a great contributor to the team that’s put this together. Now, if we look at the screen where I left off, you’ll notice the navigation … “

At the end of the day, hijackers are usually known quantities in an organization and when they do it repeatedly and predictably, it’s a poor reflection on them, not you. Nonetheless, especially if you’re anticipating the possibility of being hijacked, then you would be wise to plan ahead with the suggestions I shared above. Good luck out there!

by Beth Levine | Apr 17, 2017 | preparing for a presentation, procrastination, public speaking

The other day, as I was wrapping up part two of a three-part presentation skills training program, I gave the group their assignment for the mock presentations they are scheduled to deliver during the third and final phase. I think it’s fair to say that the 18 or so faces in front of me did not look excited, so I found myself saying: “Please don’t dread these presentations. They’re going to be much more fun and beneficial than you think. Look at them as an opportunity, a gift … yada yada yada.”

Ugh, since when did I become just like the dentist? That’s what the faces seemed to convey to me – the upcoming mock presentations evoked the same dread as impending dental work.

The reality for this group, however, is that being given the chance to work on their presentation skills in a safe, friendly, supportive environment is an opportunity and a gift. They are part of a leadership development program in their company and therefore have been identified as super high-potential professionals deemed worthy of the investment of time and money. Their skills are being cultivated in many areas critical to their future success, presentation skills being just one.

If I had been thinking on my feet a little better that day, I would not have said, “Please don’t dread these presentations.” Here’s what I would have said instead and here’s what everyone in a high-potential career situation needs to think about:

“Welcome to the big leagues! In the big leagues, you guys will go up against some of the best in the business, and there is no doubt your communication and presentation skills will be one of your key differentiators. So, let’s talk about you getting in the right head space for this next and final phase of our training.

“Welcome to the big leagues! In the big leagues, you guys will go up against some of the best in the business, and there is no doubt your communication and presentation skills will be one of your key differentiators. So, let’s talk about you getting in the right head space for this next and final phase of our training.

No one in the big leagues wastes time dreading an at bat. Rather, they spend their time imagining a home run, being fully prepared to deliver a stellar performance, and embracing the moment when it comes. That’s what I want all of you to do as you get ready for your presentations – imagine success, prepare for it, and come into the room like it’s Opening Day and you are being given an opportunity to shine!”

That would have been a heck of a lot better than imploring the group not to dread it. Lesson learned … by me, this time!

by Beth Levine | Jan 5, 2016 | procrastination, public speaking

res·o·lu·tionˌrezəˈlo͞oSH(ə)n/ noun 1. a firm decision to do or not to do something.

res·o·lu·tionˌrezəˈlo͞oSH(ə)n/ noun 1. a firm decision to do or not to do something.

It’s that time of year. For as many people as I know who make resolutions about physical fitness, I seem to know just as many who make resolutions about communication skills.

If you have been kicking yourself and muttering any of the following under your breath over the past year – “I need to get some coaching, I need to be a better communicator.” Or, “Next time, I want to go in there and knock their socks off.” Or, “Okay, this year I’m going to work on my presentation skills.” – you’ll want to read on.

There’s no magic bullet and no one-size-fits-all coaching remedy to help you be a better communicator or presenter. There is, however, one really important, knowledgeable, insightful person already in the mix – you! – and so I’m designating you as your own coach.

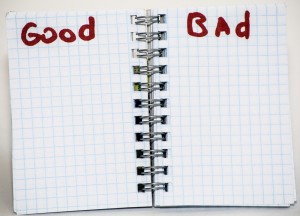

And here’s how I suggest you begin – 1) read, and 2) make two lists. Pretty simple. Read this blog, read others, read whatever you can get your hands on that’s relevant to you and your career and the venues in which you communicate. Then make two lists – one to keep track of what you want to start doing differently, and the other to keep track of what you want to stop doing.

According to the dictionary definition, the word resolution implies an intention to change. Change is much easier said than done. That’s why in order to make it doable, you’ll want to be more specific than “I want to be a better communicator” or “I want to get some presentation skills coaching.” You’ll want to break it down into “starts and stops,” so that you can itemize and track what change looks like for you.

Be a keen and objective (well, as objective as possible) observer of yourself and others. Check in with your lists once a month or so, adding new insights and ideas on the “start list” and hopefully crossing off old and bad habits from the “stop list.” Be fair and honest with yourself, and relish even the smallest “starting” and “stopping” victories.

Remember: Communication is the currency of your success. You exchange words and ideas more often than you exchange money. Make your communications as valuable as you possibly can this year!

by Beth Levine | Nov 3, 2015 | preparing for a presentation, procrastination, public speaking

Mistakes, accidents, and breaches of reputational integrity happen. And when they do, there is an urgent duty for an organization to respond. Lawyers and crisis communications advisors huddle to hash out what the Communicator in Chief – usually the CEO – can and should say. While these occasions almost always call for #transparency and #graciousness, in the end, what comes out of the top executive’s mouth is up to him or her.

Mistakes, accidents, and breaches of reputational integrity happen. And when they do, there is an urgent duty for an organization to respond. Lawyers and crisis communications advisors huddle to hash out what the Communicator in Chief – usually the CEO – can and should say. While these occasions almost always call for #transparency and #graciousness, in the end, what comes out of the top executive’s mouth is up to him or her.

Recently, s^*t happened to Volkswagen and, while the CEO lost his job over the company’s widespread deception, the #transparency and #graciousness of his initial response might help save VW in the court of public opinion. The biggest obstacle facing VW now is regaining public trust, which will only happen if the company continues to communicate with the open and gracious language that the former CEO Dr. Winterkorn used as soon as the crisis began. [Read it here.]

Two other major public crises offer a study in contrasts for when s^*t happens (excerpted below from Jock Talk: 5 Communication Principles as Exemplified by Legends of the Sports World):

Johnson & Johnson CEO James E. Burke was widely praised for handling one of the worst corporate crises in one of the best and most proactive ways during the Tylenol poisoning episode in 1982. Seven people, including one child, died from cyanide-laced Tylenol pills in the Chicago area. From a crisis management point of view, Burke’s actions and words were exemplary. In response to the 1982 events, he ordered one of the first massive product recalls, pulling 31 million bottles (with a retail value of $100 million) of the nation’s best-selling pain reliever from shelves across the country and replacing them as soon as possible with what was at the time a brilliant innovation: tamper-resistant packaging, a quick-turnaround company initiative that Burke personally oversaw. The entire effort saved the Tylenol brand and reinforced J&J’s reputation and i ts long-term shareholder confidence.

From a communication standpoint, Burke was lauded for making himself available and accessible to the media during the crisis and for offering comments that were marked by compassion, genuine concern for the public’s safety, and open acknowledgment of the importance of the public’s trust. “People forget how we built up such a big and important franchise,” said Burke. “It was based on trust.”

In subsequent decades, Burke was showered with accolades for saving and rebuilding a brand and the corporation behind it and for his candor in the face of a crisis that threatened to take down both. In 2000 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton, and three years later Burke was recognized by Fortune magazine as one of history’s ten greatest CEOs. Yet despite all of the attention and acclaim accorded him, in 2003 Burke reflected on the crisis: “When crises occurred that we never could have foreseen, our customers stuck by us in ways we never could have imagined. A company credo that put customers first and shareholders last ultimately benefited both groups.” Burke’s comments contained subtle deflections of praise along with a sincere sharing of recognition with others. Graciousness and leadership. Period.

In stark contrast, let’s look at the public remarks of former BP CEO Tony Hayward following the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010. When the explosion and sinking of an oil rig caused dangerous and unprecedented amounts of oil to spill into the Gulf of Mexico, the company took many of the right communications measures, including apologizing and reassuring the public through ads and public statements. But then came the CEO’s career-defining gaffe: In the face of loss of lives and livelihoods, Hayward said, on camera, “There’s no one who wants this thing over more than I do, I’d like my life back.” His lack of self-awareness and sensitivity concerning his audience met such broad criticism that Hayward resigned and was replaced a few short months after the incident.

In the face of difficulty, there is always room for a leader to step in and frame public discourse or sentiment. This is similar to what clergy do when they deliver a eulogy, offering the comfort and perspective their audience needs in that moment of loss. You, as a leader in an organization, will no doubt face moments when your audience is counting on you to tell them what they should do with their mixed, confusing, or sad feelings. And if the moment is big enough, what you say should be something that will help them move forward and that will endure.

Do you get nervous about speaking in public? Sometimes? Always? Let’s see what we’re even talking about here.

Do you get nervous about speaking in public? Sometimes? Always? Let’s see what we’re even talking about here.

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of

Talking, I have realized, is overrated and overused (ergo, the gospel of

Last week, I was delivering a workshop on Executive Presence and Communication to a group of high-potential executive women at a large financial services firm. As always, I encouraged the group to share relevant stories and anecdotes at any time during our half-day together.

Last week, I was delivering a workshop on Executive Presence and Communication to a group of high-potential executive women at a large financial services firm. As always, I encouraged the group to share relevant stories and anecdotes at any time during our half-day together. “Welcome to the big leagues! In the big leagues, you guys will go up against some of the best in the business, and there is no doubt your communication and presentation skills will be one of your key differentiators. So, let’s talk about you getting in the right head space for this next and final phase of our training.

“Welcome to the big leagues! In the big leagues, you guys will go up against some of the best in the business, and there is no doubt your communication and presentation skills will be one of your key differentiators. So, let’s talk about you getting in the right head space for this next and final phase of our training. res·o·lu·tionˌrezəˈlo͞oSH(ə)n/ noun 1. a firm decision to do or not to do something.

res·o·lu·tionˌrezəˈlo͞oSH(ə)n/ noun 1. a firm decision to do or not to do something. Mistakes, accidents, and breaches of reputational integrity happen. And when they do, there is an urgent duty for an organization to respond. Lawyers and crisis communications advisors huddle to hash out what the Communicator in Chief – usually the CEO – can and should say. While these occasions almost always call for #transparency and #graciousness, in the end, what comes out of the top executive’s mouth is up to him or her.

Mistakes, accidents, and breaches of reputational integrity happen. And when they do, there is an urgent duty for an organization to respond. Lawyers and crisis communications advisors huddle to hash out what the Communicator in Chief – usually the CEO – can and should say. While these occasions almost always call for #transparency and #graciousness, in the end, what comes out of the top executive’s mouth is up to him or her.